The Hidden Editor: How Goscinny Saved the English Asterix

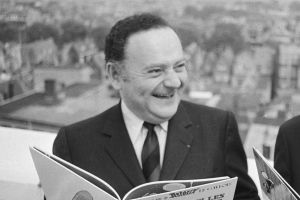

When English-speaking readers open an Asterix album, they often assume the linguistic magic comes entirely from the translators. But during the formative decades of the series, one man stood quietly behind every English speech bubble, every reimagined pun, and every carefully calibrated joke: René Goscinny himself.

Fans rightly celebrate Goscinny as the scriptwriter who gave Asterix its wit, structure, and narrative heartbeat. Far fewer realise that—up until his death in 1977—he also personally read, reviewed, and approved the English translations. His involvement wasn’t ceremonial. It shaped the tone that English readers now instinctively recognise as “Asterixian,” and it set the creative benchmark for every translator who followed.

1. The Context: Why Goscinny Got Involved

When Asterix first attempted to cross the Channel, the results were… uneven.

- The Valiant Serialization: In the early 1960s, the British comic Valiant ran a heavily altered version titled Little Fred and Big Ed — a complete rebranding that stripped away the Gallic-Roman setting and the wordplay that defined the original.

- Literal Early Translations: Other pre-Bell attempts tried to translate Goscinny’s French-language puns literally. French humour often relies on phonetic tricks, names-as-jokes, and cultural references. Unsurprisingly, these early literal translations fell flat in English.

Goscinny, ever protective of his creation, understood the problem immediately: Asterix couldn’t be translated word-for-word. It needed to be adapted with the same comedic intent, rhythm, and irreverence found in the French originals.

Fortunately, he was uniquely qualified to supervise such an adaptation.

2. The New York Years: A Creator Fluent in Anglo Humour

Goscinny’s English-language instincts didn’t come from phrasebooks or schoolroom grammar; they came from real immersion. From 1945 to 1949 he lived in New York City, working in advertising and illustration. During this time he befriended American cartoonists—including figures linked to the emerging satirical style later epitomised by MAD Magazine.

This period mattered. It meant:

- His English was fluent, not functional.

- He understood Anglo-American comedic rhythm, timing, and deadpan delivery.

- He could read the translators’ manuscripts directly and assess not only accuracy but whether the joke actually landed.

According to later interviews with translator Anthea Bell, Goscinny read their English drafts with ease and focused on what mattered most: the humour, not literal fidelity.

3. Bell, Hockridge, and the Birth of the “High–Low” English Voice

When Anthea Bell and Derek Hockridge were brought on as translators, they faced an impossible challenge: how to translate French puns that simply could not be carried over.

Their solution was radical—and brilliant.

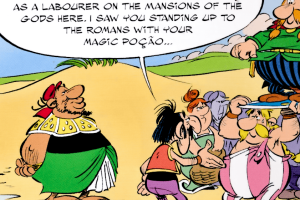

The Strategy: Contrast

- Visuals: The Gauls look rustic, rowdy, and wonderfully chaotic.

- Text: The English dialogue would be witty, polished, and knowingly sophisticated.

This contrast produced a distinctly British “high–low” comedy tone that became a hallmark of the English editions. Some describe it as “upper-class-twit” humour; more precisely, the translators drew from a P. G. Wodehouse–inspired voice for narration and some Roman dialogue. This gently pompous register created a new comedic friction that English readers adored.

When Bell and Hockridge presented this approach, Goscinny didn’t push back. He welcomed it. He recognised that this stylistic choice was the English-language equivalent of his own French wordplay—a way to preserve the spirit rather than the syllables.

4. The Art of Transcreation: Names, Puns, and Permission

The collaboration between Goscinny and his translators produced some of the most beloved character names in world comics. Since literal translation wouldn’t work, Bell and Hockridge applied creative “transcreation”—and Goscinny approved.

| French Original | Meaning | English Name | Why It Works |

|---|---|---|---|

| Panoramix | “Panoramic view” | Getafix | Double meaning: “get a fix” (joke about the potion) + problem-solving. |

| Assurancetourix | “Comprehensive insurance” | Cacofonix | Switches pun type to directly reflect his awful singing. |

| Idéfix | “Fixed idea / obsession” | Dogmatix | Plays on “dogmatic”—stubborn and canine. |

These English names weren’t compromises—they were new jokes, tailored to English sensibilities while respecting the original humour. And crucially, Goscinny read and signed off on them.

5. A Legacy of Creative Synergy

The resulting English Asterix wasn’t a translation in the usual sense. It was a three-way collaboration:

- Goscinny ensured the humour survived the journey.

- Uderzo guarded the visual pacing, panel beats, and playful typography.

- Bell & Hockridge crafted English wordplay worthy of the originals.

After Goscinny’s sudden death in 1977, his direct oversight naturally ended. But by then, the tone was set. Bell and Hockridge continued translating with the confidence and creative licence he had encouraged from the beginning.

This is why, even today, English-language Asterix doesn’t feel like an import. It feels like a version written for English readers, not merely translated for them.

Conclusion: The Invisible Hand That Shaped a Classic

René Goscinny’s role in the English editions of Asterix was never announced, credited, or requested by readers—but it was decisive. His fluency, comedic instincts, and willingness to embrace creative adaptation ensured that the humour survived the jump from French to English.

Thanks to his guidance, Asterix became one of the rare European comics whose English versions stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the originals. And long after his passing, the tone he fostered continues to echo through every pun, every name, and every well-timed British quip in the English Asterix canon.

The hidden editor may be gone, but his comedic fingerprints remain on every page.

Anthea Bell’s last Asterix translation was Asterix and the Missing Scroll; the next album, Asterix and the Chariot Race, was translated by a different translator (Adriana Hunter). Nanette McGuinness is responsible for the recent US English translations.