2500 Years of Art History in Four Panels

In Asterix and the Laurel Wreath, Albert Uderzo delivered a quick visual lesson in Western art history, condensed into a brilliant few panels of slapstick. Deep within a Roman slave market run by the merchant Typhus, a slave pitches his “versatility” to prospective buyers by adopting a series of dramatic poses. These comical contortions are, in fact, meticulous parodies of four of the most world-renowned classical and modern sculptures.

Page 16 of Asterix and the Laurel Wreath showcases the comic’s signature blend of period satire and clever anachronism, juxtaposing the Roman setting of 50 BC with masterpieces spanning nearly twenty centuries.

1. The Anachronistic Ponder: Le Penseur (The Thinker)

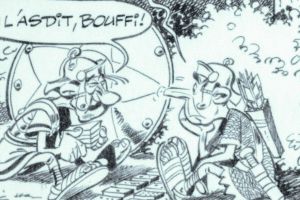

The sequence opens in Panel 1 with the most delightfully jarring anachronism. The slave, seated and leaning forward with his chin resting squarely on his fist, strikes the unmistakable pose of Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker (Le Penseur).

Background on the Sculpture: Rodin, a leading figure in 19th-century French sculpture, conceived The Thinker between 1880 and 1882. It was originally a much smaller piece intended to represent the poet Dante Alighieri observing the circles of Hell from the top of Rodin’s monumental bronze doorway, The Gates of Hell. Over time, Rodin enlarged the figure and gave it independence, allowing it to symbolize not just a specific poet, but the universal human condition of deep thought and contemplation. The immense tension in the figure’s muscular body, even in repose, suggests a profound intellectual struggle—a weighty concept hilariously reduced to a marketable skill in the Roman slave market.

2. The Classical Stance: Contrapposto and Imperial Associations

In panels 2 and 4, the slave rises into a highly statuesque pose defined by the Greek concept of contrapposto. This weight-shifted stance—where the body is supported mainly by one leg, creating the natural, subtle S-curve along the torso—was the standard for idealized human representation from the Classical Greek era onward.

As this is a typical, academic demonstration of posture, it is impossible to know if Uderzo had a single specific statue in mind. However, the slave’s regal, high-status bearing strongly suggests the visual language of Roman power. This posture brings to mind the Augustus of Prima Porta , and if this link was intended, the joke acquires a brilliant satirical layer: a slave is parodying the highest possible authority—that of Augustus, the adopted son and eventual successor of Julius Caesar. The slave’s mimicry of the Imperial line is the ultimate piece of irony, fulfilling the auctioneer’s cry for a display of “class and distinction.”

3. The Height of Agony: Laocoön and His Sons

Panel 3 presents the slave in his most dramatic state of struggle. With a twisting torso and a raised leg, he fights against a rope, which ingeniously substitutes for the venomous sea serpent. This pose is an exact parody of the Laocoön Group.

Background on the Sculpture and Discovery: This monumental marble group depicts the tragic fate of the Trojan priest Laocoön and his two sons, who were devoured by serpents sent by the gods after Laocoön warned the Trojans about the wooden horse. Attributed by the Roman writer Pliny the Elder to three Rhodian sculptors—Hagesander, Polydoros, and Athanadoros—the work is a masterpiece of the Hellenistic period (or an early Imperial Roman copy of a Hellenistic original).

Characterized by its intense emotional expression, theatrical movement, and highly detailed anatomy, the Laocoön Groupwas admired in antiquity. Its rediscovery in a vineyard in Rome in 1506 had a profound impact on Renaissance artists, most famously Michelangelo, serving as the quintessential icon of human agony and drama in Western art.

4. The Athletic Ideal: Diskobolos (The Discus Thrower)

The final pose (Panel 5) captures the slave bent backward, rope in hand, perfectly mirroring the tension and grace of Myron’s Diskobolos (The Discus Thrower).

Background on the Sculpture and Style: Created around 450 BC by the Greek sculptor Myron, the Diskobolos is one of the most iconic works of the High Classical period. Myron’s genius lay in his ability to freeze a moment of explosive athletic action—the brief pause just before the discus is thrown—while maintaining the serene composure and harmony typical of classical ideals. The athlete’s face remains calm, contrasting sharply with the tremendous physical coil of his body.

Like the Doryphoros, the original bronze sculpture is lost, and the work is known through numerous Roman marble copies. The statue perfectly encapsulates the Greek artistic principle of rhythmos (harmony and balance), transforming a fleeting competitive moment into an enduring symbol of athletic perfection.

The Originals

All taken from Wikipedia

Conclusion

By having his Roman slave effortlessly transition between the contemplation of the 19th century (The Thinker), the mathematical perfection of 5th-century BC Greece (Doryphoros), the dramatic Hellenistic agony (Laocoön), and the balanced action of the Classical era (Diskobolos), Uderzo crafted a multi-layered joke that remains one of the most brilliant Easter eggs in the entire Asterix series.