The Roman Army Explained

Ranks, Formations, and Battle Strategy in Caesar’s Time

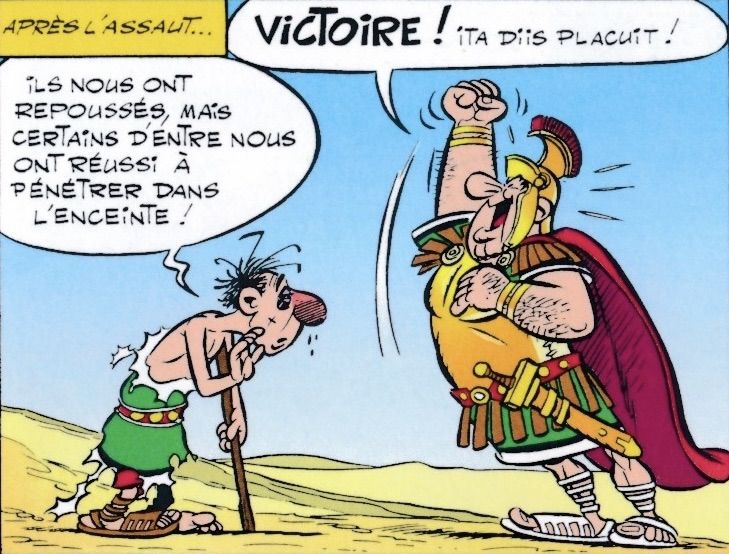

When we read Asterix, we often meet Roman soldiers commanded by stern-looking centurions or see mentions of legions and cohorts. But what do those words actually mean? Behind the humor of the comics lies one of the most sophisticated military systems of the ancient world. By the time of Julius Caesar’s conquest of Gaul, around 50 BCE, the Roman army had already undergone centuries of evolution and was on the brink of even greater changes under the emperors. To understand what a “centurion” really was, or why Roman legions seemed unstoppable, we need to look at how this army developed, how it worked in Caesar’s day, and how it changed afterward.

From Citizen Militia to Professional Soldiers

Rome did not begin with a professional standing army. In the early Republic, citizens were called up to fight much like a militia. They were organized in a Greek-style phalanx at first, but by the fourth century BCE Rome developed a more flexible system: the manipular legion. Soldiers were arranged in three lines according to age and wealth—the hastati at the front, the principes behind them, and the veteran triarii as the last reserve. This formation, known as the triplex acies, gave Roman commanders more room to maneuver than the rigid phalanx.

Over time, however, this system showed its limits. As Rome expanded, campaigns grew longer and more distant, making it difficult to rely on short-term citizen service. By the late second century BCE, reforms traditionally associated with Gaius Marius created a more professional force. Property requirements for service were dropped, which meant even Rome’s poorest citizens could enlist. Equipment became standardized, soldiers trained year-round, and the cohort replaced the smaller maniples as the main fighting unit. Soldiers now carried their own gear on the march, earning the nickname “Marius’ mules.” By the time Caesar entered Gaul in 58 BCE, these reforms had produced the legion that would dominate the Mediterranean.

The Legion Under Caesar

A legion in Caesar’s time usually numbered about 4,800 heavy infantry, though numbers could vary. It was divided into ten cohorts, each of which was made up of centuries of around 80 men. The first cohort was larger and contained the most experienced soldiers. Supporting them were the auxiliaries: non-citizen troops who provided cavalry, archers, and slingers. Together, legionaries and auxiliaries created a balanced force capable of both shock action and flexibility.

Each legion was commanded by a legatus, appointed by the overall commander—Caesar himself, in Gaul. Beneath the legate were several tribunes, junior officers from the senatorial and equestrian classes, and the praefectus castrorum, responsible for logistics and camp organization. The true backbone of the legion, however, was the centurionate. A centurion commanded a century, but his responsibilities went far beyond numbers. He drilled his men, kept order, led them in battle, and enforced discipline. The most senior centurion of a legion, the primus pilus, advised the commanders and enjoyed considerable prestige.

The army also depended on specialists. Standard-bearers such as the aquilifer, who carried the legion’s sacred eagle, and the signifer, who held unit standards, served as rallying points in battle. Signalers with horns and trumpets transmitted orders over the noise of combat. Engineers, medics, and clerks—known as immunes because they were exempt from regular fatigues—kept the army functioning as an efficient machine.

Equipment and Daily Life

The legionary of Caesar’s time carried the classic tools of Rome’s military success. His large rectangular shield, the scutum, provided excellent protection. He wore chain mail armor, the lorica hamata, while helmets of the Montefortino or Coolus types protected his head. His primary weapons were the pilum, a heavy javelin designed to bend on impact and make enemy shields useless, and the gladius, a short sword ideal for stabbing in close quarters. A dagger, the pugio, served as a sidearm.

Life on campaign was not all about fighting. Each day, the army constructed a fortified camp (castra), complete with ditches, ramparts, and neatly organized streets. Soldiers dug, built, and maintained fortifications as routinely as they marched or fought. These camps not only offered security at night but also symbolized Roman order imposed on foreign landscapes.

Training, Discipline, and Rewards

What set the Roman army apart was not only its equipment but also its discipline. Soldiers trained with heavier wooden weapons to build strength and drilled constantly in marching, formation maneuvers, and mock battles. Discipline was strict, with punishments ranging from fines and extra duties to flogging. In extreme cases, units that showed cowardice could be decimated—one man in ten executed by his comrades.

Yet Rome balanced harshness with rewards. Soldiers could earn decorations (dona militaria) such as phalerae (medals) or torcs (neckrings) for bravery. Victorious generals promised land, cash, or citizenship, particularly to auxiliaries. Such incentives tied soldiers’ loyalty closely to their commanders, one reason figures like Caesar could inspire such devotion.

On the Battlefield

When battle came, the Roman army relied on a simple but effective sequence. Skirmishers might harass the enemy first, after which legionaries advanced in good order. At close range they unleashed their pila, breaking enemy lines and making shields heavy and awkward. Immediately after, they charged with swords drawn, pressing forward in dense ranks.

The cohort system allowed flexibility. Commanders could stack cohorts for depth, spread them for width, or hold some back as reserves. Cavalry and auxiliaries protected the flanks, scouted ahead, or pursued fleeing enemies. The Romans also had specialized formations such as the testudo, where shields locked together above and on all sides to protect against missiles, though this was more common in sieges than open battles. In desperate situations, soldiers could form an orbis, a defensive circle.

Perhaps Rome’s greatest strength was in siegecraft and engineering. At Alesia in 52 BCE, Caesar’s legions surrounded the Gallic stronghold with double walls—one to keep the defenders in, the other to hold off relief forces. Such feats required discipline, engineering skill, and enormous manpower, but they showcased why Rome often won wars through endurance and organization rather than flashy charges.

After Caesar: Augustus and Beyond

The chaos of the civil wars revealed how dependent the late Republic army had become on charismatic generals. After Caesar’s assassination, his heir Augustus reorganized the military into a permanent standing army. Soldiers now served for fixed terms, usually 20 years, with standardized pay and pensions. The auxilia were formalized as separate units, and upon completing service, non-citizen auxiliaries gained Roman citizenship. Augustus also created the Praetorian Guard, an elite corps stationed near Rome.

Under the early Empire, equipment evolved further. The famous lorica segmentata, made of overlapping iron strips, became common in some legions during the first century CE, although chain mail and scale armor continued to be widely used. Later emperors adapted the army again, creating frontier troops (limitanei) and mobile field units (comitatenses) as threats shifted. Cavalry and light troops gained importance, reflecting the need to face enemies such as Parthian horse archers or Germanic raiders.

Why the Roman Army Worked

By the time of Asterix, Rome’s military system had already proven itself against Gauls, Greeks, Carthaginians, and countless others. Its success rested on a combination of factors: adaptable formations, professional leadership, relentless training, engineering excellence, and above all, the discipline of its soldiers. The centurions, the figures so often mentioned in the comics, were the linchpins of this system—tough, experienced officers who ensured that orders from generals like Caesar were carried out on the battlefield.

Quick Summary of Key Terms

-

Legion: Main Roman army unit, about 4,800 men under Caesar.

-

Cohort: Subunit of a legion, 10 per legion.

-

Century: About 80 men, led by a centurion.

-

Centurion: Professional officer responsible for training, discipline, and combat.

-

Primus pilus: Senior centurion of a legion.

-

Auxilia: Non-citizen troops providing cavalry, archers, slingers.

-

Scutum, pilum, gladius: Shield, javelin, and sword of the Roman soldier.

-

Testudo: “Tortoise” shield formation.

-

Castra: Fortified camp built daily on campaign.

The Roman army was not invincible, but in Caesar’s time it was unmatched in organization and staying power. For readers of Asterix, knowing what a centurion commanded, how a legion fought, and why Roman soldiers built a camp every night adds depth to the stories. These were the real institutions and tactics that allowed Rome to dominate the ancient world—and which still fascinate us two thousand years later.

Timeline

Early Republic (5th–4th century BCE)

-

Citizen militia, fighting in Greek-style hoplite phalanx.

-

Service based on property classes: wealthier men provided better armor.

Middle Republic (4th–2nd century BCE)

-

Shift to the manipular legion: flexible units of hastati, principes, and triarii.

-

Triplex acies formation: three lines of maniples with light troops in front.

-

Expansion across Italy and wars with Carthage tested and refined the system.

Late Republic (2nd–1st century BCE)

-

Marian reforms bring professionalism: standardized equipment, recruitment from poorer citizens, and cohorts replacing maniples.

-

Armies increasingly loyal to their generals rather than the state.

-

By Caesar’s time, legions are ~4,800 heavy infantry plus auxiliaries.

Caesar’s Era (58–50 BCE)

-

Cohort becomes the basic tactical unit.

-

Centurions form the professional backbone.

-

Daily fortified camps and disciplined engineering works support campaigns.

-

Victories in Gaul (e.g., Alesia) showcase the combination of tactics and engineering.

Augustan Reforms (27 BCE–14 CE)

-

Permanent standing army established.

-

Standard 20-year service terms with pay and pensions.

-

Auxilia formalized into distinct units, with citizenship granted after service.

-

Creation of the Praetorian Guard for the emperor.

Early Empire (1st–2nd century CE)

-

Lorica segmentata armor introduced in some legions.

-

Roman military power at its peak, garrisoning provinces across Europe, North Africa, and the Near East.

Middle to Late Empire (3rd–4th centuries CE)

-

Army reorganized to face new threats.

-

Division into limitanei (frontier troops) and comitatenses (mobile field armies).

-

Cavalry grows in importance to counter steppe horse archers and Germanic invasions.

By the 5th century CE

-

Western Roman army fragmented by political instability and economic decline.

-

Successor kingdoms in Gaul, Spain, and Italy inherited Roman military traditions, but the centralized system was gone.

Leave a comment (keep it civilised)