A Visit to Ancient Jerusalem

In Asterix and the Black Gold, Asterix, Obelix, and Dogmatix embark on a mission to retrieve a vital ingredient for Getafix’s magic potion: rock oil, known today as petroleum. Their journey takes them far from their familiar Gaulish village to the deserts of the Middle East, across Roman provinces and tribal territories. Along the way, they are pursued by Roman spies and secret agents, including the recurring character Dubbelosix. The plot mixes ancient settings with modern-day satire, including a parody of James Bond-style espionage. Published in 1981, this was the second Asterix-album written and illustrated solely by Albert Uderzo following the death of René Goscinny in 1977. The album pays subtle tribute to Goscinny, who was of Jewish descent, by giving him a cameo appearance in Jerusalem.

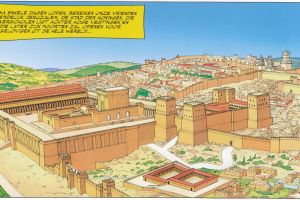

One of the most memorable illustrations in the album is a stunning bird’s-eye view of ancient Jerusalem. This scene, meticulously drawn by Uderzo, was based on the large-scale model of Second Temple-era Jerusalem that stood in the gardens of the Holy Land Hotel and now resides at the Israel Museum. The model and Uderzo’s depiction show the city as it may have looked around 50 BCE, with its grand fortifications and the central Temple complex dominating the landscape.

Jerusalem Temple

The centerpiece of the illustration is the Second Temple, standing atop the Temple Mount. At the heart of the Temple complex is the Sanctuary, or Holy of Holies, the most sacred place in Judaism. The surrounding courtyards, walls, and gates reflect the Herodian architectural style, though in 50 BCE the massive renovations by Herod the Great had not yet been completed. Jerusalem at this time was still under the rule of the Hasmonean dynasty, a Jewish priestly line that had gained independence after the Maccabean Revolt. Roman influence was growing, but direct Roman control had not yet been fully established.

Historical?

This leads to an important historical inconsistency in the album. In Asterix and the Black Gold, Roman soldiers and officials are shown operating openly in Jerusalem, and the Holy Land appears to be under Roman protection. In reality, this level of Roman presence would only occur later—first under Herod the Great as a Roman client king, and definitively after 6 CE, when Judea became a Roman province. The most dramatic assertion of Roman dominance came in 70 CE, when the Romans, under the general (and later Emperor) Titus, destroyed the Second Temple following the Jewish revolt. In Rome, the Arch of Titus still stands today as a monument to this conquest, depicting Roman soldiers carrying spoils from the Temple, including the Menorah.

Uderzo’s inclusion of Jerusalem, despite its slight anachronism, adds rich cultural and historical depth to the story. His respectful and detailed portrayal of the city reflects both artistic ambition and a gesture of remembrance. By placing René Goscinny in the midst of the Holy City—subtly immortalized among its ancient streets—Uderzo pays tribute to his late friend and collaborator in a volume that bridges humor, adventure, and history.

Leave a comment (keep it civilised)